Ketubah: The Jewish Marriage Contract and What it Really Says

Stephen P. Morse

This article appeared in the Association of

Professional Genealogists Quarterly (September 2014).

Vital records (birth, marriage, death) have always been a valuable source of family information and sought after by genealogists. The Jewish Marriage Contract (Ketubah) is no exception. The information in the Jewish record actually complements the information in the civil record: the civil record typically identifies the bride and groom by giving their family names whereas the Jewish record gives their fathers’ names instead.

There is a basic difference between the civil and religious marriage records in that one focuses on the union and the other on the termination of the union. This paper discusses what is contained in the Jewish marriage contract, tells what it really means, and provides information that can be useful to family historians.

Religion versus Tradition

There are many customs associated with a Jewish marriage, some being traditions and others being required by religious law. The bride and groom typically stand under a canopy (chupah) during the ceremony. Is the chupah required? No, it is tradition. The groom typically breaks a glass at the end of the ceremony. Is that required? No, it is tradition. The marriage is usually officiated by a rabbi. Is the rabbi required? No.

So what are the minimum requirements to make the marriage recognized by the Jewish religion? There are just two things. First, the groom says to his bride that he takes her to be his wife according to the laws of Moses and of Israel. And, second, this recital must be witnessed by two non-related Jewish men who will attest to that by signing their names as witnesses on the Jewish marriage contract. So in effect the bride and groom are marrying themselves, and two people are attesting to the fact that it happened.

English versus Hebrew

Typically a Jewish marriage contract contains two parts – one in Hebrew and one in English. All that is required is the Hebrew part. The English part is optional.

This of course assumes the marriage took place in an English-speaking country. If it occurred in a country in which French is spoken for example, substitute the word “French” for “English” throughout this paper. And if it occurred in Israel, there probably is only one part.

The Hebrew part is the same on every Jewish marriage contract, and the basic wording has been unchanged for thousands of years. Words may be added to the basic wording (see the Lieberman Clause below), but nothing may be removed.

The English part, if present, need not be an accurate translation of the Hebrew part. It might not even bear any resemblance to the Hebrew part, and could simply be vows that the bride and groom have written themselves. But typically the English part is a rough translation of the Hebrew with several liberties taken. For example, the Hebrew part talks about whether or not the bride is a virgin, and the couple might not want that information easily readable on a document that they intend to put on display. The Hebrew part also talks about how many zuzim (silver pieces) the bride is worth, which also might not be something that the couple wants to advertise.

Although I have been referring to the language as Hebrew, the contract is really written in Aramaic. But Aramaic and Hebrew use the same character set, and the words in the two languages are often similar. So referring to the language as Hebrew is not that far off.

Virgin or Not

The contract makes several references to

the bride, and typically uses one of the following terms to describe her –

virgin, widow, divorcée, or convert. It

is assumed that if the bride has never been married before, she is a

virgin. That is, virgin should not be

interpreted in the biological sense, but rather interpreted as meaning “never

been married.”

If none of the four choices are to the couple’s liking, they can always insert the non-descript Hebrew word for “bride” instead. Sorry, harlot is not one of the traditional choices.

It should be pointed out that there is an advantage to being designated as a virgin. Traditionally the amount of money that the groom sets aside for the bride is doubled. And that gets us to the next point – namely what the monetary amounts mentioned in the contract are all about.

The Ketubah is a Pre-Nup

In essence, the contract is really a pre-nuptial agreement on the part of the groom. It states how much he will give to the bride if the marriage is dissolved. However it never says that outright, but rather does so in wording that needs to be interpreted. So all the zuzim that the groom accepts and agrees to increase are in effect his divorce settlement. And he agrees to mortgage everything he owns, even the shirt off his back, in order to pay that settlement.

Here is a literal translation of the basic wording of the contract, with the fill-in terms shown in red. Read it carefully and you will see the “hidden” meaning buried in the wording.

"Be my wife according to

the practice of Moses and Israel, and I will cherish, honor, support and

maintain you according to the custom of Jewish husbands, who cherish, honor,

support and maintain their wives faithfully. And I here present you with the

marriage gift of virgins, two hundred silver zuzim, which belong to you

according to the law of Moses and Israel. And I will also give you your food,

clothing, and necessities, and live with you as husband and wife according to

the universal custom."

So far the groom has given his virgin bride a gift of 200 zuzim. That money is hers but he will hold it for her in escrow for as long as they are married.

And Goldeh, the virgin consented and became his wife. And the

property which she brought with her from her father’s house - including all

silver, gold, valuables, clothing, furnishings, and linen - Tevyeh the groom

accepted this in the sum of one hundred

silver zuzim and Tevyeh the groom

consented to increase this amount from his own property with the sum of one hundred silver zuzim, making two hundred silver zuzim in total.

Now the groom has appraised the value of his bride’s dowry at 100 zuzim, and he matched that amount with 100 zuzim of his own. This 200 zuzim also goes into the escrow account, making a total of 400 zuzim.

And thus said Tevyeh the groom:

"I accept upon myself and upon my heirs after me the responsibility to pay

this your price, this the value of your goods, and this my additional gift,

such that they will be paid from the best part of my estate and acquisitions,

all I have under the heavens, that which I own now and that which I will come

to own in the future. All my property, land and chattels, even the shirt from

my back, shall be held mortgaged to pay this price, this value of goods, and

this additional gift, during my lifetime and after my life, from this day and

forever."

The groom has just agreed to pay the

escrow money to the bride in the event that the marriage is terminated. And if he doesn’t have the money at that

time, he will mortgage everything he owns in order to raise the money. And even death is no escape because then the

responsibility falls upon his heirs.

The assumption is that the couple

will struggle their entire lives, making just enough to exist on, and not build

up any savings. It ignores the fact

that in this modern day and age the groom could go to work for a Silicon Valley

start-up and make a few million dollars on stock options. If that were to happen, he still only pays

the bride her 400 zuzim, and he keeps the millions of dollars for himself.

Tevyeh the groom has taken upon

himself the responsibility to pay this price, value of goods, and additional

gift, according to all the restrictive usages of all marriage contracts and

gifts therein which are customary for Jewish women, as enacted by our Sages of

blessed memory. It should not be regarded as a matter unworthy of consideration,

or as merely a formality.

Who, When, and Where

In addition to the body of the contract cited in the previous section, there is a lead-in section that mentions who got married, and when and where the marriage took place. The literal English translation of that lead-in is as follows:

On the first day of the week, the fourth day of the month of Tishri, in the year five

thousand seven hundred seventy two since the creation of the world,

according to our count here in the city of San

Francisco, California country of North

America, the groom Tevyeh son

of Abraham, said to the virgin Goldeh

daughter of Jacob:

The date is specified using the Hebrew calendar, such as 4th of Tishri 5772. The day and year are spelled out rather than written as digits. So the year 5772 is written as five thousand seven hundred seventy two. But that’s harder to do than you would think because in Hebrew such numbers are gender specific. The number of ten-thousands (when we get that far) is feminine, the number of thousands is masculine, the number of hundreds feminine, and the number of tens is masculine. This is further complicated by the fact that the word for thousand starts with a vowel, so the number of thousands is not only masculine, but is the liaison form of the masculine. And the words for hundred and thousand are different depending on whether the count is one (as in one hundred), two (as in two hundred) or more than two (as in five hundred). And finally, the teens are all special-case numbers, just as they are in English. With all these rules, it would be very difficult to get it right unless you spoke fluent Hebrew. Fortunately there are computer programs that can generate the numbers for us (see the Do-It-Yourself Ketubah section).

Keep in mind that the Hebrew calendar advances to the next day at sundown. So if the marriage occurs on Monday, which is normally the second day of the week, but it is after sundown, the date will indicate the third day of the week. And the day of the month will be advanced as well.

Both the groom and the bride are identified by their fathers’ given names, as in “Tevyeh son of Abraham” and “Goldeh daughter of Jacob.” Their surnames and their mothers’ names are not required. However there is nothing to prevent mentioning those names in the contract. So the groom could be identified in the Hebrew text as “Tevyeh son of Abraham Rosen and Sarah Goldstein.”

Note that the country is listed as North America. Of course that is not a country but rather a continent. However, it is often customary to write North America in place of or in addition to the actual country for marriages that occur in North America.

The Witnesses

Following the body of the contract is a final section in which the witnesses attest to what they saw transpire. The literal translation of that section is the following:

And we have performed ritual

acquisition from Tevyeh son of Abraham,

the groom, on behalf of Goldeh daughter

of Jacob the virgin,

and we have used a garment legally fit for the purpose, to strengthen all that

is stated above.

Attested to________________________________________________ Witness

Attested to________________________________________________ Witness

The witnesses must be Jewish, male, over 13 years of age, and unrelated to each other and to either the groom or the bride. And “relation” is taken to be more than just a blood relation – it includes in-laws, spouses of blood relatives, etc – basically anyone who could possibly stand to gain or lose monetarily if the union is dissolved. And if this isn't restrictive enough, the witnesses must also be Sabbath-observant. Frankly I doubt if that last requirement is often adhered to.

With all these requirements, it is sometimes hard to find two people who qualify. And the couple might have a strong desire to honor someone as a witness, even though that person might be a relative or might be female. Fortunately there is a simple way around that. The two witnesses that the couple has chosen can sign their names in English below the English text, and two qualified witnesses can sign their name in Hebrew below the Hebrew text. There is no requirement that the English and the Hebrew texts have the same witnesses, and it is the witnesses on the Hebrew text that count.

It is not uncommon for the bride and groom to be completely unaware of who signed the Hebrew portion of their contract. At my own marriage, I had asked my sister to be one of the witnesses. She obviously didn’t qualify because she was neither male nor unrelated. But at that time I didn’t know about those requirements, and the rabbi didn’t bother to tell me. My sister was one of the signers of the English portion, and that was all that I was aware of. It wasn’t until many years later, when I decided to decipher the Hebrew portion of my own Ketubah, that I discovered that my sister’s name was not there. Instead there were names of two people whom I had never heard of. They were most-likely friends of the rabbi who happened to be in the synagogue during the ceremony, and unbeknownst to me they had privately signed as witnesses in the Hebrew section. I discovered the same on my parents’ Ketubah and also on my in-laws’ Ketubah.

Note that there are only two signatures required – that of the two witnesses. The groom, the bride, and even the officiator are not required to sign the contract. However they often do, and usually they sign the English text only.

The Lieberman Clause

Traditionally a Jewish marriage can be dissolved by the

groom applying for and obtaining a Jewish divorce (Get) from the appropriate

religious authorities. The bride does not have to give her consent.

(Of course this applies to the religious marriage only – the rules for

dissolving the civil marriage are governed by the state.)

If the bride wishes to dissolve the religious marriage (because she wants to

remarry for example), she needs to ask the groom to apply for the Jewish

divorce. And that's where the inequality exists. The groom might

refuse. Or he might use this as a

bargaining point, and say that he'll apply for the Jewish divorce only if the

bride pays him a certain amount of money or agrees to certain conditions.

Whereas the bride has no such leverage over the groom when the groom is the

person wanting to dissolve the marriage.

The Lieberman clause, created by Talmudic scholar Saul Lieberman, is a clause

inserted into the contract to prevent the groom from refusing to apply for the

Jewish divorce. It has become a required part of the contract by many

conservative rabbis, but is not permitted by most orthodox rabbis.

The Lieberman clause would appear just after the main body of the contract and just before the witness section. The literal translation of the Lieberman clause is as follows:

Tevyeh son of Abraham, the groom, and Goldeh daughter of Jacob, the bride, further agreed that should either contemplate dissolution of the marriage, or following the dissolution of their marriage in the civil courts, each may summon the other to the Bet Din of the Rabbinical Assembly and the Jewish Theological Seminary, or its representative, and that each will abide by its instructions so that throughout life each will be able to live according to the laws of the Torah.

The Hebrew Text

Up to now we have been looking at the English translations of the various sections. What is especially informative is to see the standard Hebrew text of each section so that you can match it up with specific marriage contracts that you might have. Here is the Hebrew text for the example we have been using, broken up into sections.

Lead-in Section (who, when, where)

באחד

בשבת ארבעה

לחודש תשרי

שנת חמשת

אלפים ושבע

מאות ושבעים

ושתים

לבריאת עולם

למנין שאנו

מונין כאן בסן

פרנסיסקו

קליפורניה

במדינת ארצות

הברית איך

החתן טוביה

בר אברהם

אמר לה להדא כלתא גולדה

בת יעקב

Main Section (Pre-Nuptial)

הוי לי

לאנתו כדת משה

וישראל ואנא

אפלח ואוקיר

ואיזון

ואפרנס יתיכי

ליכי כהלכות

גוברין

יהודאין

דפלחין

ומוקרין

וזנין ומפרנסין

לנשיהון

בקושטא

ויהבנא ליכי

מהר כלות

כסף זוזי מאתן

דחזי ליכי מאה

ומזוניכי

וכסותיכי

וסיפוקיכי

ומיעל לותיכי

כאורח כל ארעא

וצביאת מרת גולדה כלתא דא

והות ליה

לאנתו ודין

נדוניא

דהנעלת ליה

מבי נשא

בין בכסף בין

בדהב בין

בתכשיטין

במאני דלבושא

בשמושי דירה

ובשמושי

דערסא הכל קבל

עליו טוביה

חתן דנן מאה

זקוקים כסף

צרוף וצבי טוביה

חתן דנן

והוסיף לה מן

דיליה עוד מאה

זקוקים כסף

צרוף אחרים

כנגדן סך הכל מאתיים

זקוקים כסף

צרוף

וכך אמר טוביה

חתן דנן

אחריות שטר

כתובתא דא

נדוניא דן

ותוספתא דא

קבלית עלי ועל

ירתי בתראי

להתפרע מכל שפר

ארג נכסין

וקנינין דאית

לי תחות כל

שמיא דקנאי

ודעתיד אנא

למקנא נכסין

דאית להון

אחריות ודלית

להון אחריות

כלהון יהון

אחראין וערבאין

לפרוע מנהון

שטר כתובתא דא

נדוניא דן

ותוספתא דא

מנאי ואפילו

מן גלימא דעל

כתפאי בחיי

ובתר חיי מן

יומא דנן

ולעלם

ואחריות וחמר

שטר כתובתא דא

נדוניא דן

ותוספתא דא

קבל עליו טוביה

חתן דנן כחומר

כל שטרי

כתובות

ותוספתות

דנהגין בבנות

ישראל העשוין

כתיקון

חכמינו זכרם לברכה

Lieberman Section (optional)

וצביאו מר טוביה בר אברהם

חתן דנן ומרת גולדה בת יעקב כלתא

דא דאן יסיק

אדעתא דחד

מינהון

לנתוקי

נישואיהון או

אן איתנתוק

ניש ואיהון

בערכאות

דמדינתא

דיכול דין או

דא לזמנא

לחבריה לבי

דינא דכנישתא

דרבנן ודבית

מדרשא דרבנן

דארעתא דקיימא

או מאן דאתי

מן חילה

וליצותו

תרוייהו

לפסקא דדיניה

בדיל דיכלו תרוייהו

למיחי בדיני

דאורייתא

Witness Section

דלא

כאסמכתא ודלא

כטופסי דשטרי

וקנינא מן טוביה בר אברהם

חתן דנן למרת גולדה בת יעקב כלתא

דא על כל מה

דכתוב ומפורש

לעיל במאנא

דכשר למקניא

ביה והכל שריר

וקים.

נאם _________________________________________ עד

נאם _________________________________________ עד

Paragraphs and Sentences

If you look at any Jewish marriage contract, one of the first things you’ll be struck by is the fact that there are no paragraphs. There aren’t even any periods, so it all appears to be one big run-on sentence. And the document is block justified (aligned on both the left side and the right side).

All that is done intentionally. The lack of paragraphs and the block justification eliminates any short lines. Recall that this is a legal contract (a pre-nuptial agreement). A short-line would provide room for a person to insert words or phrases after the document was signed.

Here is the preceding example, with no paragraphs and with block justification.

באחד בשבת ארבעה

לחודש תשרי

שנת חמשת

אלפים ושבע

מאות ושבעים

ושתים

לבריאת עולם

למנין שאנו

מונין כאן בסן

פרנסיסקו

קליפורניה

במדינת ארצות

הברית איך

החתן טוביה

בר אברהם

אמר לה להדא כלתא גולדה

בת יעקב הוי

לי לאנתו כדת

משה וישראל

ואנא אפלח

ואוקיר ואיזון

ואפרנס יתיכי

ליכי כהלכות

גוברין יהודאין

דפלחין

ומוקרין

וזנין

ומפרנסין

לנשיהון

בקושטא

ויהבנא ליכי

מהר כלות

כסף זוזי מאתן

דחזי ליכי מאה

ומזוניכי

וכסותיכי

וסיפוקיכי

ומיעל לותיכי

כאורח כל ארעא

וצביאת מרת גולדה כלתא דא

והות ליה

לאנתו ודין

נדוניא

דהנעלת ליה

מבי נשא

בין בכסף בין

בדהב בין

בתכשיטין

במאני דלבושא

בשמושי דירה

ובשמושי

דערסא הכל קבל

עליו טוביה

חתן דנן מאה

זקוקים כסף

צרוף וצבי טוביה

חתן דנן

והוסיף לה מן

דיליה עוד מאה

זקוקים כסף

צרוף אחרים

כנגדן סך הכל מאתיים

זקוקים כסף

צרוף וכך אמר טוביה

חתן דנן אחריות

שטר כתובתא דא

נדוניא דן

ותוספתא דא

קבלית עלי ועל

ירתי בתראי

להתפרע מכל

שפר ארג נכסין

וקנינין דאית

לי תחות כל

שמיא דקנאי

ודעתיד אנא

למקנא נכסין

דאית להון

אחריות ודלית

להון אחריות

כלהון יהון

אחראין

וערבאין

לפרוע מנהון

שטר כתובתא דא

נדוניא דן

ותוספתא דא מנאי

ואפילו מן

גלימא דעל

כתפאי בחיי

ובתר חיי מן

יומא דנן

ולעלם

ואחריות וחמר

שטר כתובתא דא

נדוניא דן

ותוספתא דא

קבל עליו טוביה

חתן דנן כחומר

כל שטרי

כתובות

ותוספתות

דנהגין בבנות

ישראל העשוין

כתיקון

חכמינו זכרם לברכה

וצביאו מר טוביה בר אברהם

חתן דנן ומרת גולדה בת יעקב כלתא

דא דאן יסיק

אדעתא דחד

מינהון

לנתוקי

נישואיהון או

אן איתנתוק

ניש ואיהון

בערכאות

דמדינתא

דיכול דין או

דא לזמנא

לחבריה לבי

דינא דכנישתא

דרבנן ודבית

מדרשא דרבנן

דארעתא דקיימא

או מאן דאתי

מן חילה

וליצותו

תרוייהו

לפסקא דדיניה

בדיל דיכלו

תרוייהו למיחי

בדיני

דאורייתא דלא

כאסמכתא ודלא

כטופסי דשטרי

וקנינא מן טוביה בר אברהם

חתן דנן למרת גולדה בת יעקב כלתא

דא על כל מה

דכתוב ומפורש

לעיל במאנא

דכשר למקניא

ביה והכל שריר

וקים.

נאם

_________________________________________ עד

נאם _________________________________________ עד

A Typical Approximate Translation

As already mentioned, the English portion of the contract is usually not a literal translation of the Hebrew. The following English texts captures the flavor of the Hebrew wording without going into the details of the bride’s virginity or how much the groom paid for her. Such a text, or something similar, is often used for the English portion of the contract.

On the first day of the week, the fourth day of the month of Tishri in the year five thousand seven hundred seventy two since

the creation of the world, according to our count here in the city of San Francisco, California, corresponding to

the second day of the month of October in the year two thousand eleven, the holy covenant of

matrimony has been entered into between the Bridegroom Tevyeh son of Abraham

and his Bride Goldeh daughter of Jacob.

The said Bridegroom made the following declaration to his Bride. "Be thou

my wife according to the law of Moses and Israel. I faithfully promise that I

will be a true husband unto thee. I will honor and cherish thee, work for thee,

protect and support thee, and to provide all that is necessary for thy

sustenance, even as it becometh a Jewish husband to do. I also take upon myself

all such further obligations for thy maintenance, during thy lifetime, as are

prescribed by our religious statute."

And the said Bride has plighted her troth unto him, in affection and in

sincerity, and has thus taken upon herself the fulfillment of all the duties

incumbent upon a Jewish wife.

This covenant of marriage was duly executed and witnessed this day, according

to the usage of Israel.

Attested to________________________ Witness

Attested to________________________ Witness

A Do-It-Yourself Ketubah

Now that you understand the various parts of the Ketubah, you’ll begin to realize that it shouldn’t be too hard to make your own. Not only will that save you hundreds of dollars, but it will allow you to customize the appearance and the wording of the contract to be exactly what you want.

There are three steps to making your own Ketubah. The first is obtaining a blank Ketubah (devoid of text) that has a design that you like. The second is generating the English and Hebrew text of your choice. And the third is combining the two.

There are various free blank and filled-in Ketubahs on the web. If you find a Ketubah design that you like and it already contains text, you can always blank out the existing text using your favorite photo-editing program. A large collection of Ketubah designs from around the world can be found at the National Library of Israel website: http://web.nli.org.il/sites/NLI/English/collections/jewish-collection/ketubbot/Pages/default.aspx .

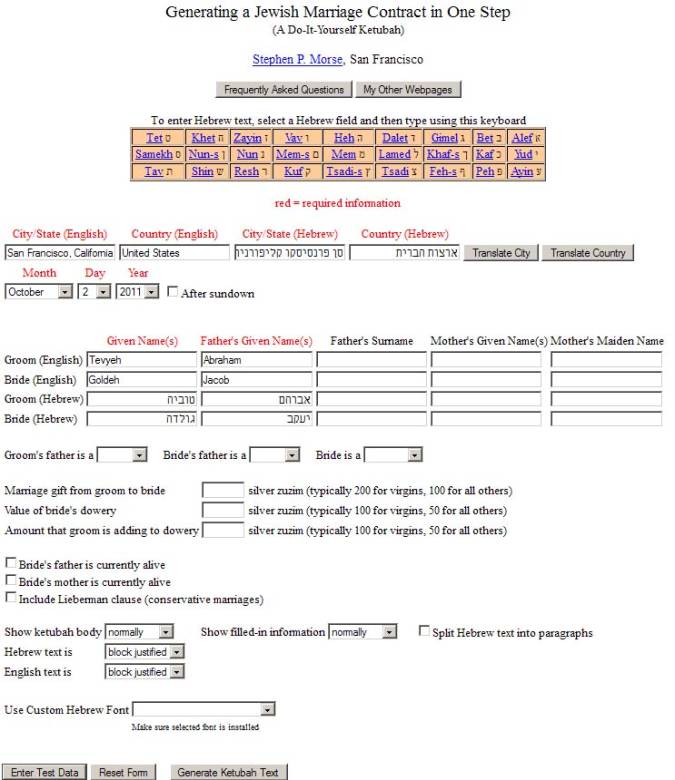

As for generating the English and Hebrew texts, there is a free tool on my One-Step website that can help you: http://stevemorse.org/ketubah/ketubah.html. You fill out a form specifying the information about your particular wedding (date, place, names of bride and groom). Once you’ve completed the form, you press a button and your desired Hebrew text and English translation will appear.

After you have your blank Ketubah and your desired text, you use your favorite photo-editing program to copy-and-paste the text onto the blank Ketubah.

Disclaimer

This paper is based on my own understanding of what the Jewish marriage

contract is all about. I do not claim to be a religious scholar, and I

know I'll take a lot of criticism, especially from rabbinical circles, for some

of the statements that I have made.